Tuesday, July 29, 2008

Vitaliy Katsenelson: HMOs, Heal thyself!

My brief comments and disclaimer: I own UNH and plan to add to my position on dips hopefully in the low 20's and high teens as the US election looms. My target price is $60/share based on a DCF analysis similar to this one by Dr. Price. I don't think that this company is a "great" one and don't plan to hold it for the very long term: it is known for treating its employees and clients very poorly. I do think that it is extremely undervalued (due to the emotional reaction many investors have towards the company?), even considering worst case political outcomes.as Vitaliy elaborates on below. Don't forget that the "vital few" agree with recognition of this value: Warren Buffett, Chris Davis and Edward Owens are amongst 9 gurus who own substantial amounts of UNH stock (WE recently bought at $47/share, adding to a 6.4 Million share holding).

You Don’t Have to Be Sick To Own HMO Stocks: UnitedHealth Group, WellPoint and Aetna

July-29-2008

[b]Vitaliy N. Katsenelson column: [/b]You want to buy straw hats in the winter. This sums up an important kernel of successful value investing: making decisions (buying and selling) that are unpopular at the time. (Of course, one has to make sure that, due to global climate change, winter is not swiftly followed by an ice age. In the case of the stocks I am about to discuss, today is winter and the summer will come again.) Shares of [b]UnitedHealth Group (UNH)[/b] and those of its HMO comrades have declined significantly over last six months. UNH has taken down its earnings guidance twice in 2008 from $3.90 to about $3 per share. Competition among HMOs is intensifying; the weak economy is not helping, as employers are looking for ways to save money and downgrading their health care coverage. HMOs have underestimated their medical costs. Of course, the rising unemployment is hurting enrollments and adding more pressure to an already sobering situation. So that is the bad news. Everybody knows it. HMOs' current, ex- (and there are plenty of those) and future shareholders know it. The bad news is more than priced into these stocks. With single-digit price-earnings ratios, HMO stocks are priced as if the sun will never to shine again, as if a lunar eclipse became a permanent celestial feature for the industry. UNH, as well as [b]WellPoint (WLP), Aetna (AET)[/b] and others, are priced as if they were going out of business. They are not! The sun will shine again. The baby boomers are getting older and are consuming more and more medical services. For good or bad, the HMO's role in the health care industry is unlikely to diminish. The industry has changed dramatically over the past decade. It consolidated. Now the top five companies account for roughly 80% of industry revenues. With fewer players, the more rational their behavior should be (read: stable pricing). The price war that took place in late 1990s, when the industry was very fragmented, and was responsible for record low margins, is unlikely to take place, at least to the same degree, this time around. Also, instead of trying to fight ever-rising costs of health care and getting a bad rap from consumers, HMOs are focusing on two things: 1) exercising tremendous buying power by extracting lower prices from health care providers and 2) embracing the inflation in medical costs by taking a cost-plus approach to pricing; in other words, passing medical inflation on to consumers. In the short run, as is apparent from recent announcements, both the "cost" and the "plus" parts are going in the wrong direction. The industry underestimated the recent rise in medical costs, and the weak economy has been (temporarily) detrimental to pricing. The value of a company is the present value of its discounted future cash flows. Thus, a great way to judge a company's worth is through the discounted cash flow model, which projects future cash flows and discounts them back at particular rate. Even if we project significantly lower, declining future cash flows (an unlikely scenario), we will still get intrinsic values that are higher than today's depressed stock prices suggest. Finally, there is a political risk--the elephant in the room. We have a presidential election and a strong Democratic candidate with a social agenda. This is bad for the HMO stocks, right? Well, though HMO stocks may have starred as villains in Michael Moore's movie Sicko, they are not at the core of the health care crisis and are likely to be a part of the solution. Public health care companies have generated $250 billion in revenues and $13 billion in profits in 2007. This may sound like a lot of money, and it is, but that only represents a net margin of 5% and a return on capital of 5%. Neither number screams, "We're fleecing the public!" In fact, they are close to the economics of government- regulated electric utilities. Let's say politicians decide to go after HMOs. They only have $13 billion of profits to work with; even if they halve HMOs' profitability, $6.5 billion will not solve trillion-dollar health care problems. Also, 81% to 83% of these companies' revenues go to paying for health care services (doctors, hospitals, drugs) and another 3% to 4% of revenues fall into Uncle Sam's pockets. It is hard to milk this industry for political gain. At the same time, if the new head of government decides to fix the health care problem by insuring the 45 million uninsured Americans, government will call on--you guessed it--the private sector HMO industry. HMO stocks look ugly in the short term, and the news flow may get worse before it gets better. But these stocks are trading at incredibly attractive valuations, have strong financial positions and great cash flows. Though they don't pay meaningful dividends, they are using every ounce of tremendous free cash flow to buy back stock. At today's depressed prices this could make a meaningful difference. In the case of UNH, the company can buy roughly 17% of its outstanding shares a year from its free cash flows. The short-term negatives--and I believe they are short term in nature--may be a blessing in disguise.

You Don’t Have to Be Sick To Own HMO Stocks: UnitedHealth Group, WellPoint and Aetna

July-29-2008

[b]Vitaliy N. Katsenelson column: [/b]You want to buy straw hats in the winter. This sums up an important kernel of successful value investing: making decisions (buying and selling) that are unpopular at the time. (Of course, one has to make sure that, due to global climate change, winter is not swiftly followed by an ice age. In the case of the stocks I am about to discuss, today is winter and the summer will come again.) Shares of [b]UnitedHealth Group (UNH)[/b] and those of its HMO comrades have declined significantly over last six months. UNH has taken down its earnings guidance twice in 2008 from $3.90 to about $3 per share. Competition among HMOs is intensifying; the weak economy is not helping, as employers are looking for ways to save money and downgrading their health care coverage. HMOs have underestimated their medical costs. Of course, the rising unemployment is hurting enrollments and adding more pressure to an already sobering situation. So that is the bad news. Everybody knows it. HMOs' current, ex- (and there are plenty of those) and future shareholders know it. The bad news is more than priced into these stocks. With single-digit price-earnings ratios, HMO stocks are priced as if the sun will never to shine again, as if a lunar eclipse became a permanent celestial feature for the industry. UNH, as well as [b]WellPoint (WLP), Aetna (AET)[/b] and others, are priced as if they were going out of business. They are not! The sun will shine again. The baby boomers are getting older and are consuming more and more medical services. For good or bad, the HMO's role in the health care industry is unlikely to diminish. The industry has changed dramatically over the past decade. It consolidated. Now the top five companies account for roughly 80% of industry revenues. With fewer players, the more rational their behavior should be (read: stable pricing). The price war that took place in late 1990s, when the industry was very fragmented, and was responsible for record low margins, is unlikely to take place, at least to the same degree, this time around. Also, instead of trying to fight ever-rising costs of health care and getting a bad rap from consumers, HMOs are focusing on two things: 1) exercising tremendous buying power by extracting lower prices from health care providers and 2) embracing the inflation in medical costs by taking a cost-plus approach to pricing; in other words, passing medical inflation on to consumers. In the short run, as is apparent from recent announcements, both the "cost" and the "plus" parts are going in the wrong direction. The industry underestimated the recent rise in medical costs, and the weak economy has been (temporarily) detrimental to pricing. The value of a company is the present value of its discounted future cash flows. Thus, a great way to judge a company's worth is through the discounted cash flow model, which projects future cash flows and discounts them back at particular rate. Even if we project significantly lower, declining future cash flows (an unlikely scenario), we will still get intrinsic values that are higher than today's depressed stock prices suggest. Finally, there is a political risk--the elephant in the room. We have a presidential election and a strong Democratic candidate with a social agenda. This is bad for the HMO stocks, right? Well, though HMO stocks may have starred as villains in Michael Moore's movie Sicko, they are not at the core of the health care crisis and are likely to be a part of the solution. Public health care companies have generated $250 billion in revenues and $13 billion in profits in 2007. This may sound like a lot of money, and it is, but that only represents a net margin of 5% and a return on capital of 5%. Neither number screams, "We're fleecing the public!" In fact, they are close to the economics of government- regulated electric utilities. Let's say politicians decide to go after HMOs. They only have $13 billion of profits to work with; even if they halve HMOs' profitability, $6.5 billion will not solve trillion-dollar health care problems. Also, 81% to 83% of these companies' revenues go to paying for health care services (doctors, hospitals, drugs) and another 3% to 4% of revenues fall into Uncle Sam's pockets. It is hard to milk this industry for political gain. At the same time, if the new head of government decides to fix the health care problem by insuring the 45 million uninsured Americans, government will call on--you guessed it--the private sector HMO industry. HMO stocks look ugly in the short term, and the news flow may get worse before it gets better. But these stocks are trading at incredibly attractive valuations, have strong financial positions and great cash flows. Though they don't pay meaningful dividends, they are using every ounce of tremendous free cash flow to buy back stock. At today's depressed prices this could make a meaningful difference. In the case of UNH, the company can buy roughly 17% of its outstanding shares a year from its free cash flows. The short-term negatives--and I believe they are short term in nature--may be a blessing in disguise.

Saturday, July 26, 2008

Stock Market Hangover: A hair of the dog

Wednesday, July 23, 2008

When 1 + 1 = 3

There are many different ways to approach this technique and most are not appropriate for the long term small retail investor (i.e. us).

The 2 special situations that are relatively safe and lower maintenance include:

- buying holding companies that own equities whose market values, when added together, far exceed the current share price of the holding company. Another way to say this is that it is trading at a deep discount to NAV.

- exploiting corporate "spin-off" opportunities: a large company breaks itself up into a number of smaller companies to unlock value unappreciated by the market prior to the breakup.

It's unbelievable to me that these situations can actually exist when there is so much "smart money" floating around-- you'd think the opportunity would come up and disappear within seconds as there are so many professional money managers scouring the market 24/7 looking for this kind of stuff.

Peter Lynch explains in his book "One up on Wall St." that institutional money is highly constrained from taking advantage of special situations that put the odds heavily in favour of the small indpendent investor:

- The "window dressing" effect-- in order to make their performance numbers match the market and the competition come RRSP/401K time each year (you better believe their job relies on that) the money managers purposely sell stocks with remarkable long term potential but have suffered a short term set back and buy stocks that have momentum i.e. buying high and selling low or buying expensive and selling cheap

- Brokerage/Company rules requiring at least 2 analysts to give a favourable report on the company AFTER the spin off. This is like assuming that the spun off companies are like brand new public companies... complete unknowns even though they often function exactly like they did before with the same clients and the same management as pre-spin-off. Garnering analyst attention and a published analysis usually takes months.

- Most money managers will choose a mediocre return or even a loss in popular (= expensive, usually!) house hold name companies than a superior return over the long term in an initially obscure company. This way when they defend their investment choices to their clients (particularly the professional ones), the blame can be attributed to external forces.

- Most pension funds have rules preventing investment in small cap stocks or in any equity that does not come from a committee approved list. As everyone knows, nothing good has EVER come from committee (unless one or two people do all the work and everyone else lets them)

- Last but not least, when a bear market sets in, investors often panic and this leads to large and rapid redemptions from mutual funds, hedge funds and even pension funds. Unless the fund is sitting on a large wad of cash, it MUST sell stocks immediately to fund those redemptions no matter what the price currently is and no matter what brilliant strategy the manager has in place.

Take comfort that for once, you have an advantage over the "big guys" on Wall and Bay St.

l

Tuesday, July 22, 2008

More pain?

QUARTERLY LETTER

Published Third Quarter 2008

by Ron Muhlenkamp

The pain continues. The focus has shifted somewhat from financial concerns to the price of commodities, particularly energy and food.

One reason this is important is that increasing prices for food and energy affect nearly everyone worldwide, including people in the emerging countries including (and maybe especially) China and India which have provided strong economic growth over the past number of years. This increases the odds for a worldwide slowdown/recession which could be longer and deeper than one in the United States, if the U.S. was going through this recession alone.

Parts of this picture we have seen before. In 1973-1974, the price of crude oil tripled as did the prices of wheat, corn, soybeans and a number of other commodities. The increased grain prices resulted in an increase in production which caused their subsequent prices to fall by a third within three years, their prices then stayed in that range for 30 years. The increased price of crude oil drove efforts to improve energy efficiency. In the U.S. and other countries, we now use half the energy per dollar of GDP that was used in 1970! We expect much of this pattern to occur again – but it takes time.

Meanwhile, another factor has helped to complicate the process. Because commodity prices have gone up, a number of investors have concluded they can benefit from buying commodities as an investment. And they’ve allocated a portion of their assets to that end. This is similar to buying Internet stocks in 1999 because they’d gone up; in 2005 it was houses; and in 2006 it was Chinese and Indian stocks. Such actions are self-fulfilling, for a while. We believe these actions are currently driving the price of crude oil. The difficulty is in knowing when and at what level it will rollover.

This uncertainty, in the marketplace, is putting downward pressure on nearly all stocks, even some that should benefit from the increased prices in commodities (e.g., both Deere and Exxon are down over the past six months). While this pressure is presenting us with the best investment values we’ve seen in a decade, the pressure is likely to continue until we see a crack in the price of crude oil.

Wednesday, July 16, 2008

Definite Entertainment

Today bank shares popped like cheap champagne. Wells Fargo was up 30% and USB topped 17% in a single session. CRAZY! who ever heard of huge blue chips making moves like this so quickly?

The factors at play here are multiple for sure: an SEC that is finally enforcing the rules about naked shorts (brokerages loaning out shares that they actually don't have) in the financials, the energy specter no longer looking quite as scary (bring oil prices down) and the market finally recognizing that it hasn't seen valuations of the cream of the crop businesses this low for almost 20 years (1990).

I think its important not to take these trends to0 seriously--- unless they offer an opportunity to buy the companies that you've been researching even more cheaply than in the past.

Shares I have bought in my companies' name at 52 weeks lows in the last 3 weeks:

AXP

MKL

LYG

Y

NYX

OCX (my wife's RRSP)

KMX (not a financial but what the heck)

I'm planning to add to the BBSI position soon--- hoping it dips below $10/share.

l

Filed Under: WFC,

Filed Under: WFC, Filed Under: WFC,

Wells Fargo is not exactly a tiny neighborhood bank. With $366 Billion in assets and until recently a market cap well above $100 Billion, it's a banking heavyweight. I have owned it in many of my managed portfolios for some time. Mr. Buffett also owns a big slug.

Long an exceptionally well-run bank, WFC largely avoided most of the sub-prime mess, but they are still exposed to some questionable home equity loans. So when they announced better than expected results this morning and increased their dividend 10%, the stock reacted favorably.

Actually, that's a bit of an understatement. The stock absolutely blasted off, rising nearly 33%! The last move anywhere near this big for WFC was after the crash of 1987 when it rose 15% in a day. Of course its market cap was a fraction of what it is today. In fact, its market cap increased by $22B (!) today on > 5x normal trading volume, closing on its highs. Wow.

My best guess is there was a "bit" of short covering involved here. The amazing thing is if the shorts can get squeezed this badly in a stock as big and liquid as WFC, what's going to happen in some of the smaller, illiquid, heavily (and likely naked) shorted stocks when the coast really does begin to look clear? Look out above! Sure, many of these stocks probably deserve to be shorted into oblivion. But in my opinion many don't.

As always I have no clue when this will happen. Maybe today is the start. More likely, it is just another bear marker rally, but who knows. Certainly none of the talking heads believe that today marks the start of anything sustainable - a good reason in itself to believe that it might. Whenever it does happen though, I think it's likely to be a violent and extended rally.

Sunday, July 13, 2008

Saturday, July 12, 2008

Think that you're contrarian by betting against the market?

have a look at the two charts presented there. Many of the stocks there have >50% of the float as short interest! The repeal of the "uptick rule" of 1929 mandating that a stock price had to increase a bit before subsequent short sales occurred last fall is likely a major contributor to this phenomenon.

The next few months/quarters should be very interesting as the inevitable short covering rush/squeeze occurs. This type of market position is not sustainable IMHO.

Posco PKX: Cold Korean Steel

An amazing Q2 profit has lead to a share price rally out of the bargain zone. I'm hoping that as more concerns about global recession/depression and other gloom will knock the price back down to around $100/share where I'd definitely be interested in owning a few shares.

I'll do a full analysis later.

l

ps Couche-Tard's share price is spiralling down to my entry level: about $10/share. It closed at $11 and change Friday.

If your portfolio is taking a beating, you're among good company...

Even the Legends Are Losing in Today's Markets

- Font Size:

- Print

Yikes.

If anything reveals the difficulty of investing in today’s market, it’s the fact that investing legends have been losing money hand over fist. The market has fallen over 12% in the first six months of 2008. Meanwhile, many of the world’s greatest investors have lost more… a lot more.

The Website www.Gurufocus.com tracks the investments of the world’s greatest investors. All told, it follows 55 investors, everyone from Warren Buffett to Seth Klarman, the super secretive manager of Baupost Group, who has averaged 20% a year for more than two decades and only posted a single losing year in the bunch.

All told, only four of the 55 made money during the first six months of 2008. Let that sink in for a moment. The best of the best are losing money. Some of the biggest names in the bunch—guys like Marty Whitman and Eddie Lampert—are trailing the market by as much as 20%.

The ten worst performers were:

| Legend | 6 Month Performance |

| Marty Whitman | -43% |

| Mohnish Pabrai | -41% |

| Bill Miller | -37% |

| Joel Greenblatt | -37% |

| Eddie Lampert | -28% |

| Robert Bruce | -25% |

| Bruce Sherman | -24% |

| Charles Brandes | -24% |

| Robert Rodriguez | -22% |

| Mark Hillman | -21% |

Are these guys secretly idiots, guys who simply got lucky for a few years but really don’t know what they’re doing?

Maybe. But I doubt it.

You can underperform dramatically for a number of years and still maintain an average that beats the market over time. Richard Pzena, an investing legend in his own right, spoke about this in his 1Q08 conference call. Since the inception of his firm, Pzena Capital Management, Pzena has outperformed the market by nearly 4.5%. Here’s what he had to say about down years:

A very simple strategy, buying the lowest price-to-book stocks over the past 50 years based on the cheapest quintile of the largest 1000 stocks would have resulted in a return of about 200 times the initial investment versus about 60 times for the S&P 500. But along the way, there were 8 times you would have lost 20%.

As Pzena notes, by buying the cheapest, largest stocks in the market, you would outperform the S&P 500 by nearly threefold. However, even by focusing on the deep value portion of the market, you would still experience eight years when you’d lose 20%.

So while investing legends may be having a tough year, I have little doubt they’ll bounce back quickly. Often times the greatest test of an investor’s ability is not what he does when he’s up, but what he does when he’s down.

And I wouldn't want to make a bet against these guys.

Thursday, July 10, 2008

Barrett Business Services BBSI in depth quantitative analysis

This recent analysis (starting about half way down the page at the title Barrett Business Services, Inc. BBSI) emphasizes the excellent owner's margin = FCF/revenues. The DCF determined fair market value of $26/share v.s. todays trading price of about $10/share demonstrates an even greater discount than the time of that analysis.

l

disclaimer: I own BBSI shares.

Concept of "Owner's Margin"

Phil Fisher on Profit Margins

Phil Fisher laid out fifteen points to look for in a common stock; three of them are directly related to profit margins. Calculated as net income divided by revenue, the profit margin is a quick way to determine which companies in an industry are most efficient (i) relative to the competition, and (ii) as a whole.

Does the company have a worthwhile profit margin?

To hammer the importance of this point home, you need not look further than traditional auto manufacturers.

Does the company have a worthwhile profit margin?

Auto manufacturers have historically low profit margins. MSN Money reports a 5-year industry average of just 3.4% for auto manufacturers versus 11.5% for the S&P 500. That is, for every dollar of sales at the auto manufacturer, just $0.03 ends up in net income. The rest is spent on costs of goods sold, operational expenses, etc.

Take, for example, General Motors (GM). In its fiscal year ended December 31, 2007, General Motors reported $178.2 billion of automotive sales. To make the vehicles sold, GM reported "Automotive Cost of Sales" of $166.3 billion. Simple math would tell you that GM generated about $11.9 billion in revenue, after taking into account the cost of the materials to make the vehicles.

Here's the problem: In the three years leading up to the end of last year, GM had to spend an average of $13.7 billion on "Selling, General and Administrative" expenses — the costs to keep the lights on, to keep the salespeople motivated, to advertise, etc. $11.9 billion in, $13.7 billion out. Starting to see the problem?

When Margins are Slim

If your company doesn't have a "worthwhile" profit margin, it has a problem: When tough times surface (as they always do from time to time), weak margin companies will probably start burning cash rather than generating it. When things begin to turn around, your company's ability to generate cash will be delayed relative to its high profit margin competitors.

As your company begins to use cash rather than generate it, your ownership is in jeopardy. I'm not just talking about negative free cash flow; your company will have to sell assets, fire people, take on debt, and/or sell more stock. The result: Less sales as capacity to fill orders is diminished, lower profit margins and excess cash as interest expenses increase, and dilution of your ownership resulting in less value going forward.

Check out GM's balance sheet on Morningstar, and specifically look at the changes to shareholder equity. Here's a company that has spent the last ten years trying to keeps its head above water, struggling to find a balance between too big to be profitable and too small to maintain unit volume. When margins are too thin, the slightest breeze can knock your business around.

The Owner's Margin

Profit margins are important when looking at the industry and at historical figures for a company; the Owner's Margin looks forward.

Calculated as owner earnings (or free cash flow) divided by total revenues, the Owner's Margin can help you judge whether or not your business will be able to sustain prolonged periods of slowed sales or unusually high expenses.

In the case of General Motors, sales slipped and any excess cash they might have been able to eek out when times were good is now a pipe dream. Let's turn our attention to Pfizer.

Generating about $10.6 billion in owner earnings last year on sales of $48.4 billion, Pfizer's Owner's Margin is 22%. That is, for every dollar of sales that Pfizer recorded, it generated about $0.22 in excess cash. Think of it this way: If sales at Pfizer sank 20%, or $9.7 billion, to $38.7 billion, Pfizer would still be able to crank out more than $900 million in owner earnings without firing a single person, selling a single asset, or assuming a dime of additional debt (if it's business as usual).

A 20% hit to sales, and the company is still generating excess cash without making a single adjustment to its business? Now that's a worthwhile margin.

Of course, some adjustments would likely be made. At that level, Pfizer would definitely have to kill its $8 billion annual dividend payments (unless management wanted to foolishly assume $8 billion a year in debt to keep the dividend). Furthermore, Pfizer would likely cut staff and take other measures to return to a more worthwhile margin. Still, the company has the operational capacity to sustain a very serious hit to sales without sustaining a commensurate hit to operations or its balance sheet.

When Times Get Tough

Going back to troubled companies. If you are attributing GM's tough times to tighter consumer spending and higher gas prices, let's move out of the beaten down auto sector and move to another business — Blockbuster.

For its fiscal year ended December 31, 2006, Blockbuster reported total revenues of $5.5 billion. It generated just $183 million of owner earnings — an Owner's Margin of 3.3%. For the record, 2006 was a "business as usual" year for BBI.

Here's where it gets hairy: To generate cash and actually have any sort of value for investors, Blockbuster needs to keep sales extremely high, to keep expenses extremely low, and to operate at perfect efficiency. Any slight change can have a dramatic effect on the business.

Well, it got hairy for Blockbuster. Revenues and most expenses in 2007 were largely unchanged. However, Blockbuster's costs of sales increased by about 8%, from $2.5 billion to $2.7 billion. Owner's Margin of 3.3%; cost of sales increase of 8%. Doesn't look good for this fragile business.

Sure enough, Blockbuster's operations swung from generating owner earnings of about $183 million to requiring an additional $114 million after all expenses were paid. Its Owner's Margin dropped to a negative 2%. For every dollar of sales Blockbuster generated, it had to cough up $1.02 to keep the doors open.

In the highly competitive world of movie rentals (think Netflix, Wal-Mart, Apple TV, Comcast On Demand, etc.), a 3% Owner's Margin is definitely not worthwhile. And Blockbuster shareholders have suffered because of it.

What Is "Worthwhile"?

The term "worthwhile" is relative, and depends on your estimation of how bad things can get at your company. If you are expecting a 50% hit to Pfizer's total sales or a doubling of expenses at some point in the future, a 22% Owner's Margin is definitely not worthwhile. If, however, in the ordinary course of business and economic cycles, you would not be surprised by 10% swings in sales, a 13% or 15% Owner's Margin may very well be worthwhile.

As with everything in investing, look for a margin of safety. The higher the Owner's Margin, the better.

Random comments about the VCI portfolio

NYSE Euronext NYX has my attention now. Like most of Jim Cramer's stock picks, it is a great company that was "hot" at the time he liked it and now it is definitely not as investors assume that bear market trading volumes will continue FOREVER and also that NYX only receives income from trading (it sells market info amongst other revenue streams). It is acquiring overseas exchanges, most recently a significant portion of the Qatar Bourse. Operating margins are fat at 28%. Valuation is finally compelling with a P/E ratio (trailing) of 14 v.s. industry avg of 26 and P/B of 1.2 (1) and D:E ratio of only 0.05. I'm still doing my homework on this company but I will be sorely tempted by $40/share or less (it was trading at over $100/share one year ago and I calculate a FMV of $80/share). Downside as I see it so far is a relatively modest dividend 1.2%, the complexity of the business is very high and the future cash flows are difficult to predict as they are so levered to the markets.

Heebner comments about the big picture

Portfolio manager casts an optimistic eye on economy

July 6, 2008

Ken Heebner, a portfolio manager at Capital Growth Management in Boston, has delivered some of the best investment performances of any manager in America. He often operates as a contrarian, avoiding technology stocks in the late 1990s and betting early against mortgage companies several years ago. Heebner, 67, spoke last week to Globe reporter Ross Kerber on where the economy is heading.

There's a lot of pessimism about the economy. What's your take?

My view of the world is quite different. I think people are very concerned about our economy, they're starting to realize there could be higher inflation to come. The consensus is that we'll bring the rest of the world into our recession. But my view is we've probably seen the weakest period of economic activity. The economy may not be robust in the next year, but it's seen its low point and at some point will move higher.

That's reassuring, but how can this be?

I understand how serious the housing problem is. But it's not as broad a problem as widely perceived. It's reduced everyone's sense of financial well-being, but a third of homeowners don't have a mortgage, and the vast majority of people made down payments and have fixed-rate mortgages, so there's no financial strain. For them, the only impact is the psychological impact of declining housing prices. So therefore I don't think this is as big a deal as everyone else does. We've passed the point of maximum distress.

What evidence is there for that?

First, on manufacturing, the Institute for Supply Management's index seems to have reached a low of 49, and when this gets to 45, that's a recession. Additionally, the Fed started aggressive ly easing interest rates, and the impact of those eases will start to be felt. But I think the driver of the global economy is the developing countries, with a population of 3 billion. China, Russia, India, Brazil, and a lot of smaller countries. If you add up Japan, Europe, and the US, you're talking about a little less than 1 billion people, and you have 3 billion people going strong.

But those 3 billion have less money and less GDP. How will that drive the world economy?

These people don't have the roads, the airports, the infrastructure - and the building of these creates big demand for industrial raw materials and energy in all forms. In a nutshell, these foreign countries place a high priority on growth. The broad pattern is they're more concerned about maintaining growth than other factors, be it pollution or inflation.

Globe columnist Steven Syre has twice named you fund manager of the year, and Fortune magazine recently dubbed you "America's hottest investor." So can you talk about what you are buying and selling?

The only two stocks I've made references to [owning] in the last few months are Petrobas [Brazil's Petroleo Brasileiro SA] and Schlumberger [an oil-services company]. I'm changing the portfolios so frequently.

What do you expect US growth rates to be? And inflation?

Our economy will surprise us on the upside, growing between 2 to 4 percent over the next 12 months. I'm a bull on the US economy. Clearly housing has been a negative, but there's only four states where they walked housing prices to Never Never Land, and now it's coming back to a realistic level. Because of increasing demand from these developing economies, I can see, three years from now, inflation approaching 10 percent.

How can you be such a bull on the economy and say inflation could be such a potentially big problem?

I didn't say it's a big problem. In the 1970s and 1980s, when inflation was high - we made good money investing in stocks in that period. I'm running a portfolio. I'm not running the country. The challenge inflation presents is that price-to-earnings ratios tend to decline. So when you invest money, you want to have enough growth to offset that compression.

What impact will the outcome of the US elections have on the market?

[Barack] Obama says he wants to eliminate the Bush tax cuts and take the maximum marginal tax rates to 39.6 percent, then institute some Social Security taxes - and says he'll increase the capital gains rate, now 15 percent. That would tend to be a negative factor. It's hard to quantify, but when I think what effect the election could have on the investment world, taxation is where there's a clear difference [between the candidates]. But it would probably be easier for Obama to say, let's drill offshore for oil. That would be a huge benefit to oil-services company stocks. . . . I do think Obama's going to be elected president of the US, and the Democrats [will] win a huge victory in November.

What do you think has been the biggest surprise in the markets this year?

There was a general fear that we would fall into a recession and it hasn't done that. We've gone sideways. The big surprise is that the economy has held up as much as it has. People are overlooking the fact that we're having a huge boom in the farm economy. Also, the energy area is very positive. And I further expect the weak dollar to energize our exports and manufacturing industries. Our natural competitive strengths, our innovation and creativity, remain unique skills in the global economy. We're going to start to export cars, we'll start to export steel.

What are the biggest areas of problems for the US economy?

The brokerage firms were enjoying huge profitability because of the boom in private equity and hedge fund trading, and they won't have that. Higher inflation is always bad for insurance companies, and the banking system still has all the bad mortgage loans eroding its base. It may be a year more of that. They still have a lot more mortgages to write off.

Wednesday, July 9, 2008

Sunday, July 6, 2008

New Stock to Study: Alimentation Couche-Tard

Better known as Macs on the west coast or Circle K in the US, ATD is the second largest operator of convenience/gas bar stores in North America. Latest earnings and revenues.

- Established brand in a boring, slowly changing industry with largely predictable cash flows that tend not to be as cyclical as other consumer sectors

- 5600 stores but only 20% market share in Canada and 2% in the USA (room to grow but has sufficient economy of scale to warrant a narrow moat)

- Management's track record is excellent: smooth acquisition integration, ROE 18% highest ROC employed of all comps 20%

- Growing rapidly but not too rapidly: EPS increased by average 38%/year over the past 5 years, top line growth 51% increased yoy,

- Company remains highly profitable despite heavy pressure on margins by high gas prices and strong loonie-- if these 2 factors ameliorate a bit, earnings should exceed expectations

- Strong balance sheet with D:E ratio lowest amongst competition at 0.57. Net debt: capitalization 0.39. Well positioned to take advantage of increasingly cheap acquisitions and recent large scale divestments of Big Oil's corner stores/gas bars (Exxon has been doing this already)

- Plans for expansion into Asia under way with a deal for opening franchises in Vietnam signed last quarter

- 20% insider owned-- management and shareholder's interests squarely aligned

- 50 million dollars of shares have recently been "bought back" by the company

- Share price is markedly depressed v.s. historic valuation i.e. mean P/E of 20 now trailing P/E is 14 and FPE is 11

- minimal dividend

- secondary offers of shares have been dilutive to owner's earnings

- inflation and high fuel prices unlikely to go away anytime soon, if ever

- nuisance lawsuits v.s. the company with anti-competitive allegations seem to be popping up and may fall on sympathetic judicial ears, particularly in Quebec.

DCF calculations using 15% EPS growth for the next 5 years diminishing to 5% thereafter and assuming a 6% return on a risk free alternative investment puts the FMV stock price 5 years out as high as $66/share. I think that a more realistic target would be $25/share within the next 1-2 years.

I don't think that many would argue that at $12.75 today, this company certainly has a generous margin of safety. I would be interested in starting a position at $10/share or less in the current environment, only because I really think that there is a chance the share price could dip that low.

Other than the lack of an acceptable dividend, this company has all the attractive characteristics of a company I would love to own a piece of. Have a look at the AGM investor presentation.

Saturday, July 5, 2008

Forbes Global Value Stocks

LYG, AIG and AXP reviewed earlier in this blog. As the market carnage continues, I hope to add to all three positions as well to UNH which is dropping down to it's book value rapidly.

I'm putting together a virtual mutual fund on Marketocracy.com with to use as an educational model for a million dollar portfolio of value stocks, using the principles discussed in this blog. The ticker is VCI and the name of the fund is the Victoria Contrarian Investor's Fund. When I have it up and running, I'll post a link. Marketocracy offers a free registration and is an amazing resource of investment ideas for all investors, regardless of their style of preference. They take the top performing investor's ideas and distill them into a mutual fund that you can actually invest in, to boot.

l

Wednesday, July 2, 2008

Michael Dell

I usually watch insider trading with a somewhat detached interest but 2 recent huge trades have caught my attention:

--Michael Dell, founder and current CEO of Dell computer bought 4.5 MILLION shares at $22/share yesterday (about 100 MILLION dollars worth).

--An officer (from a well known investment co in the US as well) of the board of directors at Home Depot bought $30 million of common stock.

These aren't stock options, these are shares bought on the open market with their own pocket change just like you and I.

The significance of these trades remains to be seen; however, even to a billionaire these purchases show conviction from folks who know the business better than almost anyone else.

l

Tuesday, July 1, 2008

How to fight bear-handed

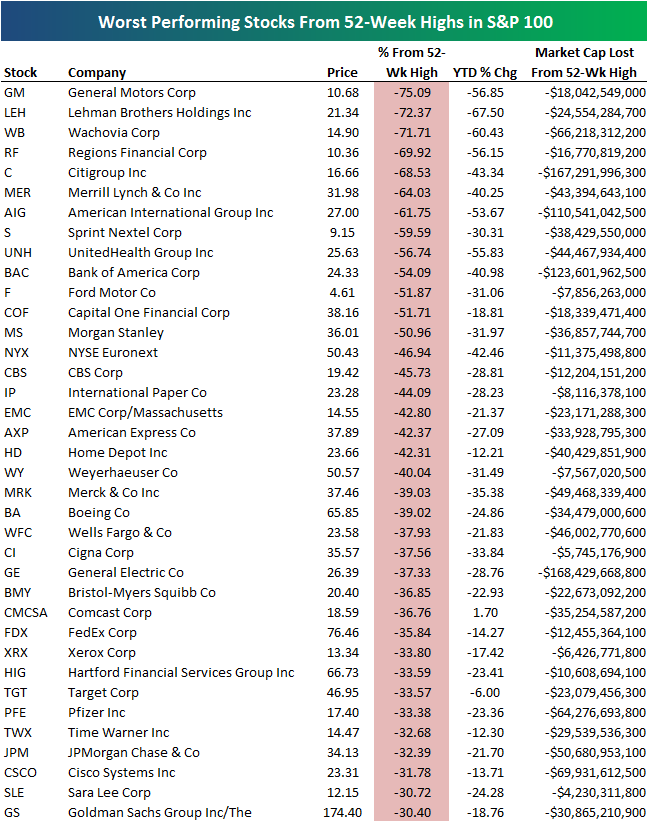

****Click on the chart above to expand it....*****

****Click on the chart above to expand it....*****Brutal, eh? Almost anyone could recognize the household names in the chart above. They are all "blue chip" stocks that brokers are supposed to be selling to orphans and widows because they are supposedly safe investments with potential for slow but sure capital appreciation combined by decent dividend yields to provide a little income. They all have large market capitalizations and many are multi-national and have wide economic moats to protect them. What's happened?

Many sane and calm-headed investors are now calling this the worst recession the USA (the world to follow) has seen since the Great Depression, mostly because of 3 negative economic forces striking simultaneously: the great deleveraging from the credit market collapse, the impressive rise in the cost of energy and food, plus the emergence of double digit inflation in most developing nations that had been (up to recently) driving global trade and economic growth. The outcome of these complex and interrelated problems cannot be predicted although it's fun to guess. I suspect that your thoughts about this have as much merit as the most erudite economist-- their track record for prediction of the start and end of bear markets is MUCH worse than a coin flip. It's not that economists are stupid or corrupt, it's just very, very hard to do and my point is: don't even try. Or if you do, just do it for fun and realize that you are participating in an intellectual exercise. Whatever you do, NEVER invest based on a gut feeling about the economic environment and where it is going. Even worse NEVER borrow money and use margin to buy based on that hunch. That's gambling and the house will win 7/10 times. The worst thing that can happen is that you will be correct and think you are a genius--- then the market will crush you.

- proven management that can execute a simple, easy to understand business plan (and have a track record at least 5 years long)

- preferably in a slowly changing industry with predictable cash flows

- have a strong balance sheet with lots of cash and little or manageable debt

- strong free cash flows (Buffett's "owner's earnings")

- a sustainable dividend that matches or exceeds the inflation rate to protect the real return of your investment

- a wide economic moat so that when the bear market blows over (whenever it does) the business emerges well positioned to take even more market share from its much diminished competitors

Two of my previous picks, Georgia Gulf Corp and Popular may crumble because of increasingly weak balance sheets and poor short term prospects. (as an aside, I have divested my shares in GCC and I have decided to hold on to BPOP because the dividend is continuing to be paid (how much longer?) and I suspect that the company's regional virtual monopoly in PR along with latino customer loyalty may sustain it to emerge virtually competitor-free.

Clarke CKI, is a favourite small cap private equity holding of mine although I have become increasingly concerned lately by the management's spending spree: they've taken Art in Motion private and bought large stakes in several other trusts as well as Liquidation World. These all may well prove to be great long term investments, particularly for such skilled catalyst/activists as the Armoyan crew. HOWEVER, the balance sheet is deteriorating and I don't like that. Over $40 million in cash has been converted to investments with poor short term prospects (particularly the market value of those investments) and as of Q1 2008 Clarke only had 2 million dollars of cash. Since that time CKI has offered to buy back $6.5 million of its outstanding 29 million common shares.... after buying sizable amounts of LW, Amisco and AIM units/shares! The only way they could achieve all of these transactions is to take on yet more debt and I calculate the D:E ratio is sitting close to 1 today. I'm not certain that depleting the cash cushion in current market conditions is prudent and I am considering paring back my position. I am reluctant to do so because I like the business plan very much. At $6.55/share CKI is trading at least 10% discount to NAV/book value; however, I feel that margin of safety for the investment has deteriorated significantly and if economic conditions on both sides of the border go even further downhill, I'm worried that little CKI will not survive.

On the other hand, Clarke Inc's big brother Onex Corp OCX is going exactly the opposite direction. It is aggressively increasing capital. Like Brookfield Asset Management (another favourite), OCX's risk management is quite clever: it uses non-recourse clauses in its financing to protect the parent holding company while positioning itself to take advantage of its markedly financially weakened targets. More on Onex in my next post....

l

Disclosure: My wife will be placing a bid for OCX shares at $29 soon.